Bringing Us the Cosmos, One Observation at a Time

On Thursday, April 24th, it will be 24 years since Hubble Space Telescope was sent skyward aboard space shuttle Discovery. It was a heady day for folks who had spent much of their careers designing and building the observatory. The subsequent discovery of spherical aberration in the mirror seemed like the end of the world at the time, but that got fixed relatively quickly and Hubble has gone on to do remarkable things.

I was about to enter graduate school when Hubble was launched. At the university, I had a job coordinating comet observations for the Ulysses Comet Watch, and my boss was one of the instrument leads for Hubble. Eventually I joined the instrument team as a very junior member, and watched as the telescope went through its difficult first years. Somewhere in that first year, I noticed that Hubble was doing science, despite its problems. That inspired me to start taking notes about those observations, and a couple of years later, I published (along with my boss, Jack Brandt, who was second author) a book called Hubble Vision (that went to two editions). I also wrote a planetarium show, which we turned into a broadcast video that went on to win a major award for science outreach in 1992.

For me, Hubble Space Telescope has been a huge part of my life, even though I wasn’t a major science user. I was part of the team, and it afforded me a seat at the table to see how Big Science was done with a Big Telescope.

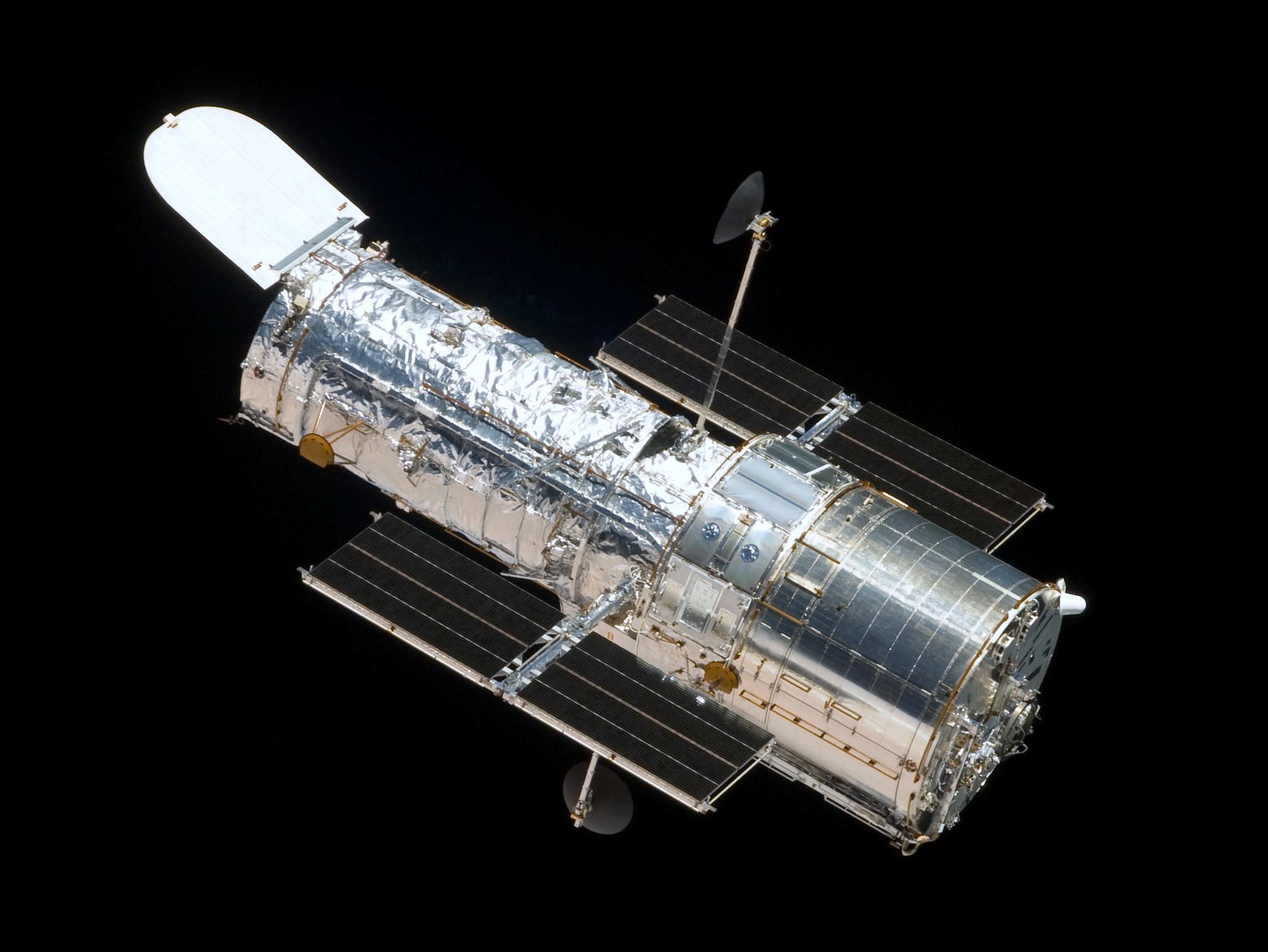

Today, Hubble is iconic. Five servicing missions have made it a useful and productive observatory. It regularly cranks out gorgeous images, high-resolution data sets, and much more. A few years ago the Space Telescope Science Institute celebrated the observatory’s millionth observation.

The sum total of those observations has been a new look at the universe. They have opened up areas of study that people didn’t expect. That serendipity isn’t something you can predict, but with any new technological advancement, you can certainly expect it.

What blows me away is that a whole generation of astronomers now entering the field have grown up knowing about Hubble, expecting to use it (or its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, or its sister observatories Chandra X-Ray Observatory, Spitzer Space Telescope, and others) and knowing that they’ll make great discoveries with it.

With Hubble, astronomers have peered into starbirth creches to spot baby stars, just starting to shine. They’ve watched as old stars die, found distant galaxies existing at a time not long after the Big Bang, and detected evidence for the mysterious dark matter that seems to permeate the universe. Oh yes, the telescope has found black holes. Lots of them. There was a time when the Institute would announce a black hole discovery, and some of us would laugh and say, “Yet another Damn Black Hole.”

That’s actually kind of staggering, that something so theoretical when I first went to college because something commonplace, due to many of the Hubble observations. So many of the discoveries made by astronomers using it have been that kind of staggering. And, the telescope’s existence has pushed astronomers to create even more sensitive instruments here on the ground, through the use of adaptive optics. So, Hubble has pushed the envelope in many ways.

Want to learn more about this observatory? Take some time to visit its Web site this week and celebrate a little by gazing at the wonderful images. They’re a small part of the huge work this telescope has done to allow astronomers to peer deeper at fainter objects to help tell the story of the cosmos.